![dabanng1]() You can tell a lot about a megastar by the way he throws his punch.

You can tell a lot about a megastar by the way he throws his punch.

A Hindi film hero might routinely fell over seven with one blow, but each has their own approach. Aamir Khan, all bloodshot eyes and biceps rippling with the fury of thousands of killed wives to avenge, brings both physical intensity and a sense of inescapable irony to the picture. Shah Rukh Khan, his every sinew straining with gargantuan effort, bellows like a wounded animal as he metamorphoses from charming lover to crazied aggressor.

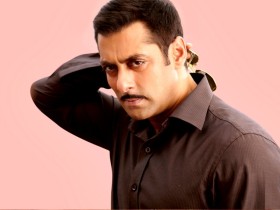

Salman Khan doesn’t bother breaking a sweat or even trying for realism as he buffets his opponents, effort be damned, smirk and quip steadily in place. The ubiquitous one-liner just underlines how one-sided the battle always is. Because Salman Khan is larger than life. And he believes it.

As do we, clearly. Earlier this year in Dabanng, Salman’s shirt tears itself off his enraged body, as if anger – and the need to show off his bare chest – are reason enough for him to suddenly turn into the Incredible Hulk. Coming at the film’s climax, the moment is dated and ludicrous beyond belief. Eternal romantic Shah Rukh would have been laughed out of theatres for trying to do the same. Aamir would have had to write a longish blog-post explaining how the scene was all a metaphor, or, somehow, Meta. Salman earned whistles, his film becoming one of the most successful in the history of Indian cinema.

In Mumbai’s Mehboob Studio, two days before that epic release, Khan sniffles his way past a ravenous pack of news-channel cameras. In no mood for niceties, he struts, chest out, upto a studio chair, parks himself on it, and turns to them. In a brutal show of strength and savvy, he preempts the questions they want to ask him, throwing out monosyllabic answers to each. “Aur kucch?” The reporters, used to standard-issue questionnaires, are flummoxed and bereft of fresh queries, and Khan is pleased as punch. He relaxes, blows his nose into a big kerchief, and swaggers out. All in less than five minutes.

He sneezes just as I walk up, clearly not in the mood but nevertheless resigned to a conversation. At this minute, eyes visibly watery, nose nearly crimson, Salman looks anything but invincible. He warily grunts through the first few questions until I ask, young man to forever-swaggering man, where on earth he meets women. “You can’t be serious,” he laughs, tired eyes instantly twinkling. Oh, but I am; he’s dated Somy Ali, Aishwarya Rai and Katrina Kaif. Is there a clandestine bar where the world’s most attractive women consistently turn up? “Ha, I wish. There isn’t a bar, dude. Otherwise we’d all go every night. I’ve… worked with them, I’ve known them. I have been fortunate with the kind of women I’ve… met. They’ve all been very nice. I’m sure you’re talking about the way they look and everything, but I mean the kind of people they are, their personalities. I’ve known them for the longest time. And as far as people, they’ve all been really beautiful.” He takes in a moment to smile. “And really loving, and really caring. Yeah, I’ve been lucky.”

Luck aside, Khan at 45 is the only single man among the industry’s megastars. “You’re single till the time you aren’t married, dude,” he interrupts instantly. I agree, wholeheartedly, but my question is how a man that powerful can gauge genuine romantic interest. Isn’t every girl awestruck? “It depends, you know,” he says, thoughtful. “The ones who’re awestruck… Nahin, yaar. Doesn’t work. Just doesn’t work,” he shakes his head.

And yet his cinema is all about invoking that very kind of awe. Is being larger than life a conscious effort? “No, it just happens. You work with good technicians. And more than that, audiences want to see things larger than life, so they make it happen.” This is clearly a position Salman enjoys, and feels he has earned. “When I started working in movies, I could never have played that character. Maine Pyaar Kiya and all, the only role I could have played was a romantic hero,” he says with a slight sneer. “From that, to come to this stage has been a long journey.” He speaks of his action-figure persona as an evolution, saying that while both romance and emotion are vital, the fights might just be the hardest part to pull off.

Even as an actor, he rates it the hardest, most challenging part. “Action is challenging for anybody. To jump, or take a punch, do all kinds of stuff, cable-work… That is more scary, because with every shot you feel something could go wrong. And you still do it. And so far, touchwood, everything has been all good. So action is the most difficult thing to do.” And in terms of performances, I ask, in terms of actual acting? Khan grins and winks. “That? It’s all good.”

Increasingly lauded for his utter lack of pretension, Khan is considered a star who often phones in his performances, barely even attempting to act. “If a film requires hard work, you work hard, yaar,” he shrugs. “If a film doesn’t require any hard work, why should you do it? If a director says ‘okay’ to a shot, okay! If he says ‘one more,’ one more!” Unlike his peers, he refuses to use terms like ‘method acting,’ to spend a shooting schedule in the skin of a character, or, sometimes, to even stop playing himself. He’s Salman Khan, and once in a while — if a director is valiant enough, or a script stirring enough, he’ll stand and deliver — but the rest of the time, it is, as he said, “all good.”

Or, at the very least, good enough for him.

~

![salman2]() Legend — and relatively credible word — has it that Salman Khan was utterly shattered when Shah Rukh Khan finagled Will Smith from Sallu’s guest-list, only to throw a party for the Hollywood A-lister at his own bungalow. Salman cut a melancholy picture at his own Smith-less party, while Smith reportedly looked somewhat bored at SRK’s party, where Salman wasn’t invited.

Legend — and relatively credible word — has it that Salman Khan was utterly shattered when Shah Rukh Khan finagled Will Smith from Sallu’s guest-list, only to throw a party for the Hollywood A-lister at his own bungalow. Salman cut a melancholy picture at his own Smith-less party, while Smith reportedly looked somewhat bored at SRK’s party, where Salman wasn’t invited.

Undeterred, Salman turned up in a motorbike, yanked Will unceremoniously, casually and instantly from the party, and before anyone could react, took him to his own. If fellow guests are to be trusted, Smith got wonderfully jiggy at the new venue.

It isn’t a very hard story to believe, Khan’s off-screen persona being that of an old-school superstar, the picture of defiance, the ultimate rebel without a cause. Depending on who you believe, he thrashes actors in bars and sends over expensive watches in morning-after apology. He is also quite the philanthropist, and judging from how he got all of Bollywood’s A-list heroines to shake their collective caboose for his Being Human charity earlier this year, he’s doing quite the bang-up job. There are whispers about his constantly roving eye, and an almost mob-like entourage which gets him ‘anything’ he points to. And then there are those who vow he’s the most honourable man in the industry.

The myth, then, is as self-contradictory as the man. The role Khan seems to fill, in fact, is that of the man-child, who thrives on indulgence, indulgence we now have to spare, being so frequently cynical the rest of the time.

“How well do you think the media knows me, or any of my closest people?,” Salman snorts, instantly sneezing hard. Battling a cold valiantly, he takes turns blowing into a formerly-white kerchief and wrapping it tightly around his knuckles, as if preparing for a street-fight. Occasionally, when thinking hard, he absently bites into it, tugging it with its teeth as if insight can be sucked out of cotton. When emphatic, he punches the air in front of his face, a phlegmatic pugilist jabbing at invisible, omnipresent opponents. “Nothing ever bothers me. Nothing.”

He says every part of the public persona is inaccurate, but he can’t be bothered to go about telling people what to think. He laughs scornfully when the aggressive, ‘bad-boy’ image is brought up. “Please. If that was there… Listen, do you hear the questions they ask me? All the time? They ask me the kind of things my own father would never ask. I don’t care, and I don’t react. The day I start reacting to it…” He trails off in a dramatically threatening voice, before winking.

“Naam, Don, Majboor, Sholay, Deewar, Zanjeer,” he rattles, with the unthinking ease of a man used to listing his favourites among his father’s screenplays. Son of Salim Khan, one-half of Bollywood’s most celebrated screenwriting pairs, Salman confesses a desire to direct. “I always wanted to direct. I really thought that I would, somewhere, make a… good… director,” he mumbles softly, before saying that he does make creative suggestions to directors he works with, but backs off because it is, eventually, their call.

“You don’t have cinema till the time you don’t have a story. You have a story to tell and you shoot the film with the worst technique, and that film will do well. And you have the best technique in the world, but the lousiest script, you can do anything you want to do but that film will not work.” So then do all the hits have strong stories? “There is something, dude,” he shrugs. “Something they like. The character, the script, something clicks, and they want to go see it. Why would they want to go see something they don’t like?”

He prides himself on his unerring script sense — “The ones that I thought will do well, so far, pretty much all of them have,” he says, saying that his thinking is that if he wants to see the film he’s making, everybody would want to see it — but that doesn’t reflect as well on his hit-loss record, with far more forgettable films showing up than actual hits. “Well yes, but the script is not usually made the way it was. They start improvising, they start changing, they get scared, yeh bhi daal do, woh bhi daal do…”

So what went wrong, then, with Veer, a film he wrote and produced earlier this year, a catastrophic failure? “First of all,” he insists, “Nothing went wrong with it at all, at the box office. But in my head, I felt a lot of things went wrong. I wanted to shoot for 18 more days.” I ask him why he didn’t, considering it was a pet project he was completely in control of, and Salman disarms me with the sort of answer no megastar could possibly dare to give.

“Dad didn’t let me,” he sighs, almost pouting. And then falls silent.

Moving on, I ask him about another bizarre Salman contradiction. “Painting?,” he grins. “Painting is a big jhol. I wanted to buy three paintings for my house. The artist charged me a lot of money, and they didn’t turn out the way I wanted them to turn out. So I thought, ‘let’s try.’ So I started painting, started getting good at it. I was fortunate to find my own style in the first five and a half, six months. Artists take the longest time to find their way to say what they want to say…”

![salman1]() Salman’s paintings are sold at exhibitions with the money going into a charitable trust, and that’s clearly what fuels his fire. “So I’m getting better and better at it, and the money’s going to a good cause.” He isn’t under many delusions about why his paintings sell. “When somebody’s buying an artist’s work, two things are important: one is the amount of experience that he has, and two is a business plan: how long is he going to be there? After that, we’re going to make so much money because we’ve gotten his art, and after he’s dead, he obviously can’t paint anymore. So,” he pauses, briefly sounding alarmingly morbid, “they make money.”

Salman’s paintings are sold at exhibitions with the money going into a charitable trust, and that’s clearly what fuels his fire. “So I’m getting better and better at it, and the money’s going to a good cause.” He isn’t under many delusions about why his paintings sell. “When somebody’s buying an artist’s work, two things are important: one is the amount of experience that he has, and two is a business plan: how long is he going to be there? After that, we’re going to make so much money because we’ve gotten his art, and after he’s dead, he obviously can’t paint anymore. So,” he pauses, briefly sounding alarmingly morbid, “they make money.”

“Here, how many paintings am I going to make anyway? I’m an actor. I paint when I find the time,” he says, explaining that it’s usually at night.

And how does he rate his own art, honestly? “If my name is not signed, it’s below average. Once my name comes down there, it’s outstanding work.” A smug grin accompanies the jab this time, the grin of a star who knows his worth. However unreal.

~

First published Rediff, December 29-30, 2010

![]()

![]()

The pallu that, in one strategic slip, changes gears from bashful to boastful. That oomph that comes from experience. That smile which knows which men to fend off and which to encourage. That wrist, miraculously flexible by years of egg-whisking. That silently leonine air that comes of controlling a pride, a brood, a household. That grace under unending pressure. That self-assuredness. That way she can always tell when the milk’s gone off. And, without question, that sheer and complete unattainability. Do we not always want who we can’t have?

The pallu that, in one strategic slip, changes gears from bashful to boastful. That oomph that comes from experience. That smile which knows which men to fend off and which to encourage. That wrist, miraculously flexible by years of egg-whisking. That silently leonine air that comes of controlling a pride, a brood, a household. That grace under unending pressure. That self-assuredness. That way she can always tell when the milk’s gone off. And, without question, that sheer and complete unattainability. Do we not always want who we can’t have? Kareena Kapoor Khan — a 32-year-old who has just married into singularly unfortunate initials — wears the pants in her relationships. At least the ones with her filmmakers. As the country’s highest-paid leading lady, she commands both banknotes and box-office openings, and has the singularly incredible star power to remain unfazed by failure. Her films may tank in theatres, may be savaged by critics, but Kareena isn’t out to prove herself, or her stardom: she walks away from the debris with her memorable chin held up, her head high, her hips sashaying invincibly past the doomed rubble of a ruinous Friday. And when the films do click, she smiles like she knew they had to.

Kareena Kapoor Khan — a 32-year-old who has just married into singularly unfortunate initials — wears the pants in her relationships. At least the ones with her filmmakers. As the country’s highest-paid leading lady, she commands both banknotes and box-office openings, and has the singularly incredible star power to remain unfazed by failure. Her films may tank in theatres, may be savaged by critics, but Kareena isn’t out to prove herself, or her stardom: she walks away from the debris with her memorable chin held up, her head high, her hips sashaying invincibly past the doomed rubble of a ruinous Friday. And when the films do click, she smiles like she knew they had to.